The ms Europa passes the Narrows …

… and enters St. John’s harbour.

Passengers in bathrobes look out as a foghorn occasionally sounds. The lugubrious bellow suddenly reminds me of my mother arriving from England on a badly battered World War Two convoy. Hours on deck in lifejackets. Now a ship filled with affluent Germans enters this same port, once key in the Battle of the Atlantic. I watch the Europa tie up and depart to find breakfast.

_________________________

Fishcakes and coffee (last night, superb scallops and pinot grigio) and a day for history in a town in which history is omnipresent.

I arrive at what can most kindly be described as an architecturally functional Royal Canadian Legion. This is the Canadian equivalent to Returned Services Associations in other Commonwealth countries. Legions here have a reputation as drinking holes, although they certainly do good community work.

But it’s what’s in front of the Legion that’s important and surprisingly - sadly - not in St. John’s official visitors’ guide. From here commenced one of the great feats in aviation history.

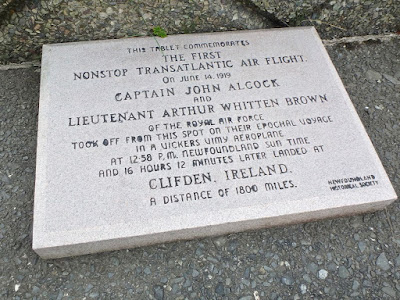

Charles Lindbergh’s undoubtedly heroic, first solo flight from mainland North America to mainland Europe is celebrated. But it has often been confused in popular memory as the first transatlantic flight. It was not.

British pilots Arthur Brown (left) and John Alcock …

… set off from here less than a year after the Great War.

Their Vickers Vimy bomber (named for Vimy Ridge, Canada’s most memorable victory in the war) lumbered across Lester’s Field …

… now Blackmarsh Road. Loaded with as much fuel as possible, the plane heaved itself into the air …

… just missing trees then at this uninspiring intersection. Next stop Ireland.

Thirteen years later, Amelia Earhart would also lift off from Newfoundland, becoming the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic.

_________________________

Now, I hope not confusingly, a battlefield in France. I’m freely borrowing from a post I wrote during a 2008 trip along the Western Front.

This is Beaumont-Hamel on the Somme where, in 1916 and minutes, much of a Newfoundland generation was destroyed.

Above are the lines of the Newfoundland Regiment. The Germans were down the slope to the left.

You can just see (clicking brings up an enlarged photo) a red sign in the distance, roughly where the enemy front lay. Even now, much of the battlefield is unsafe.

Facing a wall of fire, the Newfoundlanders advanced 'with chins tucked down as if walking into a blizzard.' By the end of the day, 310 were dead. According to the Veterans Affairs Canada website, 'Of the 780 men who went forward only about 110 survived unscathed, of whom only sixty eight were available for roll call the following day'.

St. John’s population when war began was about 32,000. Newfoundland’s population as a whole was small, most in scattered fishing settlements - outports - along the rugged and isolated coast.

The regiment alone lost 1,300 dead, some of whom lie here on the battlefield. Wartime losses meant few communities would not grieve.

Dedicated at Beaumont-Hamel in 1925, a bronze Newfoundland caribou (the regiment’s emblem) defiantly faces the German lines.

Which brings me back to the present. The sun has come out and I am at the war memorial in St. John’s.

Not only would Newfoundland lose its young, post-war would lead to near economic collapse. I sit on a low wall and think, then wander over to look at the plaque, below which are faded wreaths from this year’s July commemoration.

And learn something I never knew. Newfoundlanders fought at Gallipoli. Another waste.

_________________________

At the waterfront, fog’s gone (this is said to be the foggiest, windiest and cloudiest Canadian city) and there’s now a good view of the Narrows.

The Signal Hill tower stands out against the sky …

… the tower where, in 1901, Guglielmo Marconi received the first wireless transmission across the Atlantic. It was in Morse code, the letter ’S’ - three dots.

In the far distance Cape Spear, eastern-most point of North America. I was last there in a thick, cold fog with Charles & Diana in 1983. I well remember them uselessly, if politely, trying to see the Atlantic through an impenetrable wall of white.

In today’s weather, could we see 584 kilometres east and a few kilometres down, there would be the Titanic. Next year, should all go to plan and you have $140,000 to spare, you’ll be able to depart St. John’s and have a submarine tour of the ship.

The harbour allows me to conclude with the topic earlier raised in this post.

St. John’s in World War Two. Some ten thousand merchant ships passed through the port, although off Newfoundland more than four hundred were sunk by German U-boats. Six thousand survivors came ashore in ‘Newfyjohn’, navy slang for the city.

This was an ice-free haven with dry dock and repair facilities. An invaluable base for the Canadian and British navies to refuel, provision, rearm and win the ocean battle.

Oilfield vessels now occupy space where warships once docked. St. John’s basks in a peaceful sun and I’m done for now … gotta find some fish for a late lunch.